When I was a small boy, I was fascinated by cars. The story goes that when I was about 5, I wandered off and got lost. Somehow I ended up at the local police station, in the days of friendly bobbies on bicycles. When my parents came to collect me, I was sitting outside with a young constable identifying the make and model of every car that drove past.

Children, or boys at least, had way more freedom to roam around than anyone would consider reasonable now. When I was 7 or 8 I would wander all around Harold Hill, the huge council estate in East London where we lived. By the time I was 12 I spent whole days exploring the London red bus network on my own.

I knew all the cars that lived within a quarter mile radius of my home by heart. On an estate built for working class people, they were still fairly uncommon. Maybe one household in ten had a car, often a pre-war Austin, Morris or Ford, over twenty years old.

For a young man, earning his first wages at the Ford works in Dagenham or at one of the factories on the estate, buying a car was a dream. I'm sure it made getting dates with girls a lot easier, for one thing. But they weren't making that much money. A reasonably new full-size car was way beyond their means.

This was the era of the "bubble-car", tiny cars developed after the war for the growing market of people who wanted a car but still had limited means. A lightly-used example was perfect for the young man looking to increase his mobility, not to say pulling power.

The best known of all them is the Isetta. It indeed looked exactly like a bubble. It had no apparent doors, until you realised that the whole front of the car opened sideways, taking the steering wheel with it via a complicated linkage. A 250 cc engine could propel it to the vertiginous speed of 47 mph, though you would need plenty of room - it took 30 seconds just to get to 30 mph. There was room for two people, sitting huddled together on a bench seat. Safety was non-existent - the humans were first in line to take any impact, and back then seat-belts in cars were unheard of. The little engine was at the back under the parcel shelf. That was the only place for luggage, though there was a rack available to which a small suitcase could be strapped on the back.

The Isetta was originally Italian, built by Iso. They decided to move on to high-powered sports cars, and sold the design to BMW. Compared to the BMWs of today, this seems strange. They were also built under license in Britain, France and Brazil.

When I worked at Cisco in California, in the early 2000s, there was a vintage car club which every now and then would organise an exhibition. It was one of life's little ironies that the Isetta that showed up there belonged to the Director of Corporate Travel.

The other well known bubble-car was the Messerschmitt, built by the famous aircraft company as a diversification after the war. This was a completely different concept. It was long, thin and streamlined, rather than bubble-shaped. Entrance was via a hinged canopy, just like a fighter plane. Its two occupants sat in line, again like in a plane. Steering was through a yoke - like half a steering wheel. Once again the engine was at the back. It had an interesting way of going backwards. A single-cylinder two-stroke engine can turn in either direction, with just an adjustment to the ignition timing. This car had no reverse gear - if you wanted to go backwards you threw a switch and started the engine in the opposite direction.

The Messerschmitt is still a bit of an icon. They now sell for crazy prices - $30,000 or so for a normal one, and over $100,000 for the rarer Tiger model with four wheels and a higher-powered engine. They were quite common in films in the 1960s, and occasionally later. Probably the most famous appearance is in the Terry Gilliam film-noir, Brazil.

Messerschmitt wasn't the only aircraft company to try its hand at cars. Much less common and well-known is the Heinkel. This was very similar to the Isetta, with a sideways-opening door at the front. It was a bit less bubble-shaped, with a pointy rear-end, very recognisable to my 8-year-old bubble-car connoisseur self. There were several Isettas and Messerschmidts in the area I roamed, but only one Heinkel.

If the cars' owners happened to be around when I was passing by, they were happy enough to chat to me, especially when they realised I knew what I was talking about. That was how I managed to get a ride in something even more unusual, the Scootacar. While the others were Italian or German, this one was all British, built by the Hunslet company which had been making steam railway engines for over 50 years. Supposedly, it was designed the request of the boss's wife, who wanted something easier to park than her Jaguar.

Whereas the other bubble-cars were quite cute visually, the Scootacar was just plain weird. It was much taller, earning it the name "telephone box" at the time. Access was through a side door like a normal car. The shape supposedly came from the designer sitting on the Villiers engine it used, while an assistant drew his outline on the wall.

It would seat two people, as long as they knew each other very well. They sat pressed together astride a longitudinal bench just like a motorbike. The driver at least had the handlebar steering to hang on to, while the passenger had only the driver. About 1000 were made, so I was lucky to see one. Even this oddity has become a collectors' item, worth about £5000 now - 20 times the original cost.

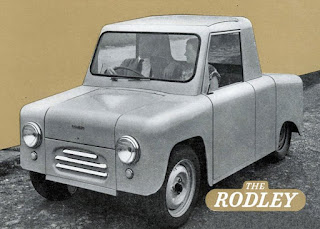

The Scootacar was at least an improvement on the designer's only previous effort at a car, the Rodley. That must have been the ugliest car ever built, all 65 of them. Many were destroyed in spontaneous fires (maybe the inspiration for the Tesla), and supposedly only one still exists. Not surprisingly, I never saw one.

There was one car in the area that was very different. One of the lads had an original vee-twin three-wheel Morgan. Now, an original 1930s model will fetch £50,000 or more. He probably picked it up for almost nothing, an ancient old-fashioned thing that nobody wanted. The thing that struck me was the engine. It was completely exposed at the front of the car, including even the valve gear on top of the cylinders. As the engine idled you could watch the valves popping open and shut on their springs. I wonder how well it dealt with bad weather.

Distinct from the bubble-cars were the two fairly common three-wheelers, looking more like small conventional cars. The Reliant was made famous by the TV programme Only Fools and Horses, but in the 50s they were acceptable family transportation, with a proper 750 cc four-cylinder engine. I saw quite a few around but they were more a car for the settled family man than for a young lad. The latter preferred the Bond Minicar, a sort of motorbike/car hybrid. It was the general shape of a car, but the mechanics were pure motorbike. The single-cylinder engine was just behind the chain-driven front wheel. To start it, you opened the bonnet (hood), and pulled a chain, like kick-starting a bike.

All of these bubble-car and minicar firms were gone by the early 1960s. The introduction of the famous Mini in 1959 didn't help them. Suddenly you could buy a serious car for not much more. My friend bought one, used of course, when we were teenagers.

As a means of transportation for the working man, motorbikes were much more common than cars. There were all the classic British makes: BSA, Triumph, Norton and others that thrived before Japanese manufacturers had the eccentric idea of building bikes that didn't leak oil continuously and need constant repairs and maintenance. For men with families, there was the sidecar, a one-wheeled pram-like vehicle that bolted onto the side of the bike to accommodate his wife and one child. I remember being taken for a short ride in one of these. Even for a small child it was overwhelmingly claustrophobic.

Not all the cars I met were bubble-cars. My parents were heavily involved in the local Pensioners' Pals, a sort of support group for the old women (hardly any men) who lived in special accommodation on Harold Hill. This brought them into contact with various local officials, doctors and so on. The Mayor of Romford was driven around in a car from a long-vanished marque, an Armstrong-Siddeley. These were the perfect cars for mayors and minor captains of industry, less ostentatious than a Rolls or Bentley but still very much a sign of being above the hoi polloi. On one memorable occasion, I even got a short ride in its luxurious padded leather interior.

In the 1950s, practically every car on the road was made in Britain and carried a British name - even if it was foreign-owned, like Ford or Vauxhaul. Foreign cars were extremely rare. While my mother was visiting one of her adopted old-age pensioners, I was wandering around and saw an immaculate dark-blue French Panhard parked on the street - recognised only from my Motor Show catalogues, of which more later. I could hardly resist taking a close look at it. It was a school day, but I'd been off with a bad cold. Suddenly I was interrupted by its owner.

"Why aren't you at school?" he demanded with authority. It turned out that he was the "School Board Man"- truant officer in American. It was his job to go around looking for children who ought to be in school, but weren't. I took him to my mother, and things were settled. But it was an awkward moment.

My aunt and uncle bought their first car when I was 7 or 8. It was a pre-war Morris 8, with the very fitting registration OLD 8. Before 1939 it hadn't occurred to people that you should be able to open the boot (trunk) to put stuff in and out. Access was by folding the rear seat. Like all small pre-war cars, it was black.

Later they upgraded to a Standard 10. This was a post-war design, so curved rather than angular, and blue-gray rather than black. It even had an opening boot - although the cheaper variant, the Standard 8, didn't, and you still had to manhandle luggage via the back seat.

In one of life's odd coincidences, my uncle was rear-ended while driving his Standard across Lambeth Bridge by his old Morris 8.

Standard used to be a major, respected British marque of cars, up until the 1960s when they "merged" with Triumph, and disappeared. Then later Standard-Triumph was absorbed by Rover, and then all went down the plughole into British Leyland. One of our neighbours had a Standard Vanguard which was, well, the vanguard of the Standard range. It was the elegantly curvaceous early-50s version, rather than the more angular design which came later. I remember him boasting to my Dad that unlike lesser cars his came with various usually-optional features including a heater.

Yes really, cars in the 1950s often didn't have heaters. When my Dad started driving vans for work, none of the earlier ones had heaters. One of my prized annual acquisitions was the Daily Express Motor Show catalogue. I only went to the show once, but my Dad bought me the catalogue every year. Apart from the cars themselves, four to a page, there were large sections of adverts for accessories. After-market heaters were common there.

My one visit to the London Motor Show at Earls Court in west London was when I was about 10. It influenced my car-buying habits for the rest of my life. I was looking at a Lancia, before they became famous for rusting away practically before you'd driven off the forecourt. I got shooed away because - obviously, as a ten-year old - I wasn't about to buy one. I vowed then never to buy one, and I never have. There was a time, in the 1970s, when Lancias were quite chic, and I might have bought one. One of my bosses had a Lancia Beta, a kind of sports hatchback. It looked very smart, although it did indeed rust away fairly quickly.

Standard wasn't the only marque that has long since disappeared. Wolseley and Riley were the luxury end of the BMC (Austin and Morris) range, with Riley supposedly being sportier. By 1960 they were just badge-engineered version of their Austin and Morris cousins. If you watch 1950s British films, the police invariably drive smart-looking Wolseleys or if they're lucky, the faster Riley Pathfinder, jangling their police bell as they drive. The whole Rootes family - Hillman, Humber, Singer, Sunbeam - were common in the 50s and 60s but completely forgotten now. Rover was the car of choice for country doctors and solicitors (lawyers). The MG name - the sporty end of BMC - still exists, but is now a nondescript Chinese car.

Returning to bubble-cars, I was amazed to discover there is a Microcar Museum, in the outer suburbs of Atlanta in Madison, Georgia. Maybe one day I'll visit and relive all my childhood memories. Maybe.

_-_15821233376.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment